Chapter 7 Intro to Data Viz

7.1 Activity 1: dplyr recap

Which function(s) would you use to approach each of the following problems?

We have a dataset of 400 adults, but we want to remove anyone with an age of 50 years or more. To do this, we could use the function.

We are interested in overall summary statistics for our data, such as the overall average and total number of observations. To do this, we could use the function.

Our dataset has a column with the number of cats a person has, and a column with the number of dogs. We want to calculate a new column which contains the total number of pets each participant has. To do this, we could use the function.

We want to calculate the average for each participant in our dataset. To do this we could use the functions.

We want to order a dataframe of participants by the number of cats that they own, but want our new dataframe to only contain some of our columns. To do this we could use the functions.

7.1.1 Data visualisation

As Grolemund and Wickham tell us:

Visualisation is a fundamentally human activity. A good visualisation will show you things that you did not expect, or raise new questions about the data. A good visualisation might also hint that you’re asking the wrong question, or you need to collect different data. Visualisations can surprise you, but don’t scale particularly well because they require a human to interpret them.

(http://r4ds.had.co.nz/introduction.html)

Being able to visualise our variables, and relationships between our variables, is a very useful skill. Before we do any statistical analyses or present any summary statistics, we should visualise our data as it is:

A quick and easy way to check our data make sense, and to identify any unusual trends.

A way to honestly present the features of our data to anyone who reads our research.

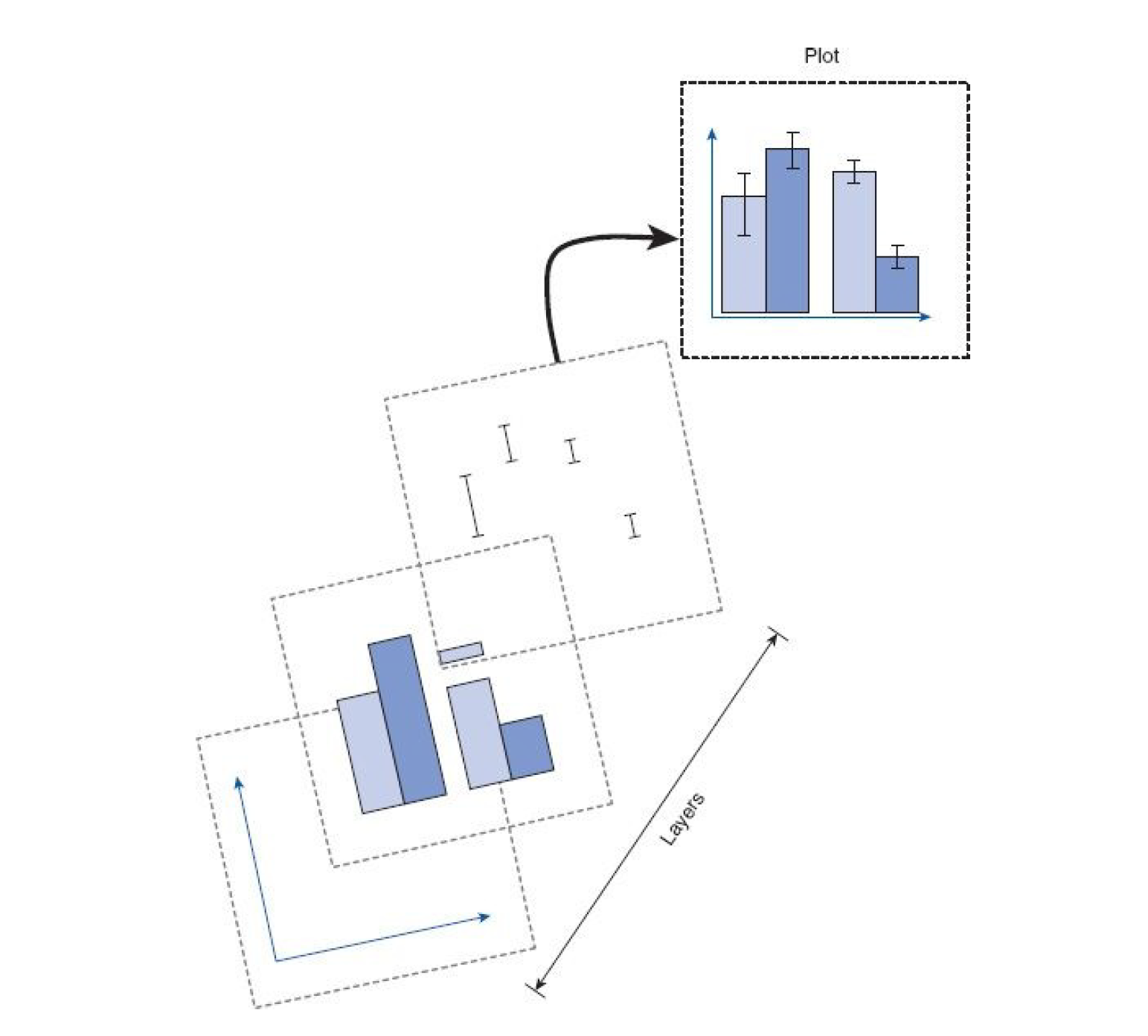

ggplot() builds plots by combining layers (see Figure 7.1)). If you're used to making plots in Excel this might seem a bit odd at first, however, it means that you can customise each layer and R is capable of making very complex and beautiful figures (this website gives you a good sense of what's possible).

Figure 7.1: ggplot2 layers from Field et al. (2012)

7.2 Activity 2: Set-up

We will use the same data files as in Loading Data when you uploaded files to the server. This data contains happiness and depression scores:

Open R Studio and set the working directory to your chapter folder. Ensure the environment is clear.

Open a new R Markdown document and save it in your working directory. Call the file "Intro to Data Viz".

Download the two .csv files above and save them in your chapter folder. Make sure that you do not change the file names at all.

If you're on the server, avoid a number of issues by restarting the session - click

Session-Restart RDelete the default R Markdown welcome text and insert a new code chunk that loads the package

tidyverseusing thelibrary()function.Type and run the below code to load the

tidyversepackage and to load in the data files in to the Activity 2 code chunk.

library(tidyverse)

dat <- read_csv("ahi-cesd.csv")

pinfo <- read_csv("participant-info.csv")

all_dat <- inner_join(dat, pinfo, by= c("id", "intervention"))

summarydata <- select(.data = all_dat,

ahiTotal, cesdTotal, sex, age,

educ, income, occasion, elapsed.days) 7.3 Activity 3: Factors

Before we go any further we need to perform an additional step of data processing that we have glossed over up until this point. First, run the below code to look at the structure of the dataset:

str(summarydata)## tibble [992 × 8] (S3: tbl_df/tbl/data.frame)

## $ ahiTotal : num [1:992] 32 34 34 35 36 37 38 38 38 38 ...

## $ cesdTotal : num [1:992] 50 49 47 41 36 35 50 55 47 39 ...

## $ sex : num [1:992] 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 2 ...

## $ age : num [1:992] 46 37 37 19 40 49 42 57 41 41 ...

## $ educ : num [1:992] 4 3 3 2 5 4 4 4 4 4 ...

## $ income : num [1:992] 3 2 2 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 ...

## $ occasion : num [1:992] 5 2 3 0 5 0 2 2 2 4 ...

## $ elapsed.days: num [1:992] 182 14.2 33 0 202.1 ...R assumes that all the variables are numeric (represented by num) and this is going to be a problem because whilst sex, educ, and income are represented by numerical codes, they aren't actually numbers, they're categories, or factors.

We need to tell R that these variables are factors and we can use mutate() to do this by overriding the original variable with the same data but classified as a factor. Type and run the below code to change the categories to factors.

summarydata <- summarydata %>%

mutate(sex = as.factor(sex),

educ = as.factor(educ),

income = as.factor(income))You can read this code as "overwrite the data that is in the column sex with sex as a factor".

Remember this. It's a really important step and if your graphs are looking weird this might be the reason.

7.4 Activity 4: Bar plot

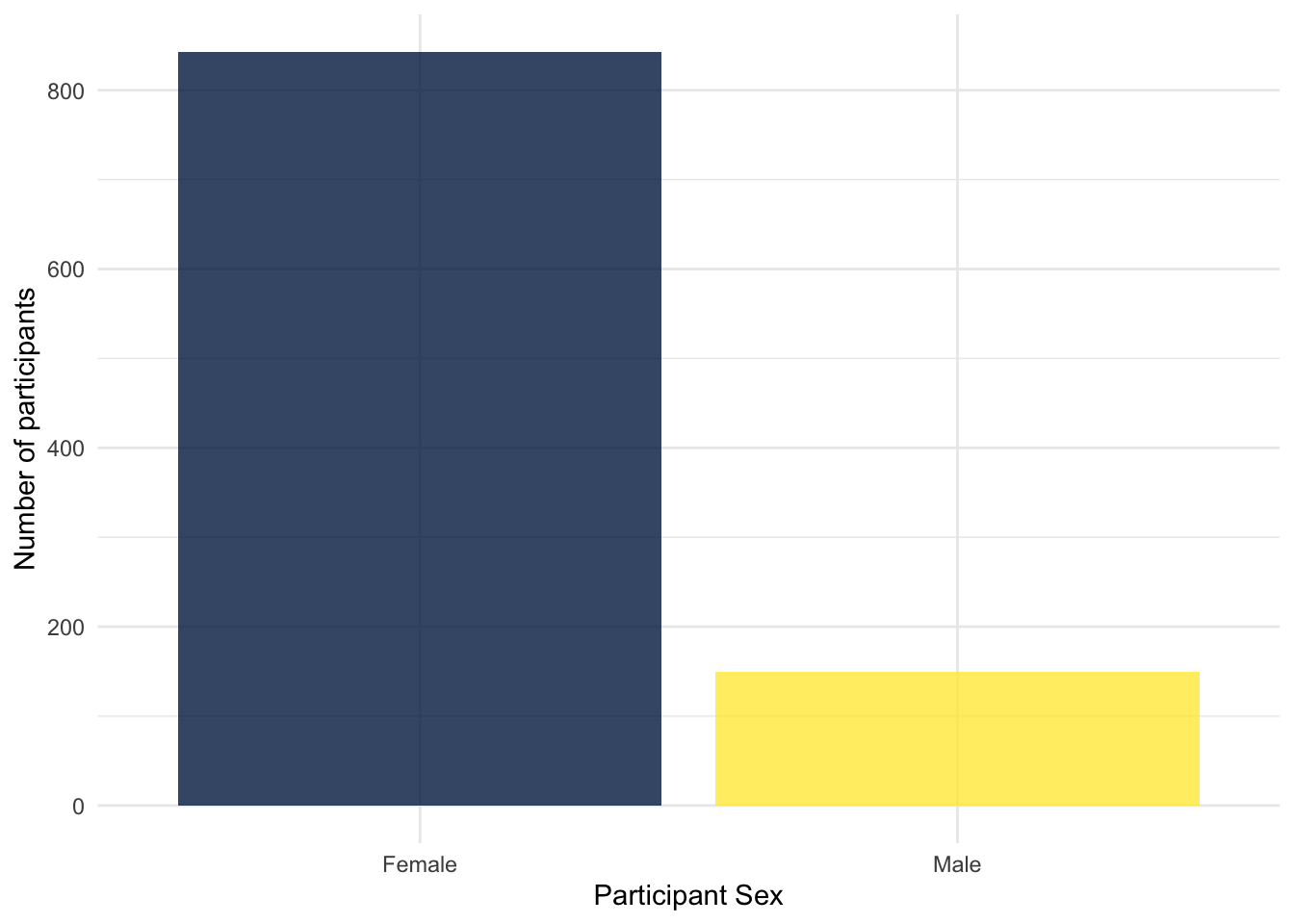

For our first example we will recreate the bar plot showing the number of male and female participants from Loading Data by showing you how the layers of code build up.

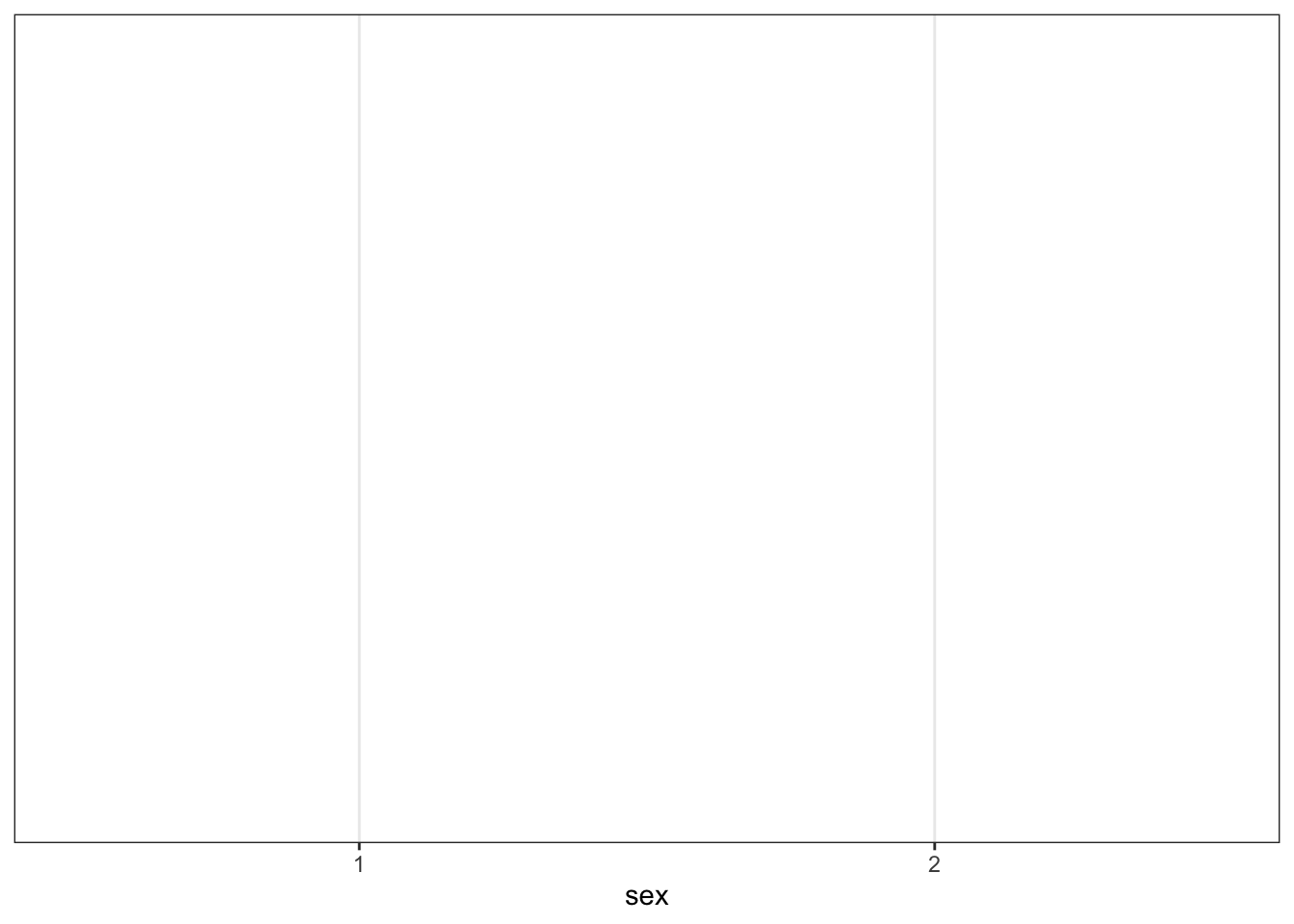

- The first line (or layer) sets up the base of the graph: the data to use and the aesthetics (what will go on the x and y axis, how the plot will be grouped).

aes()can take both anxandyargument, however, with a bar plot you are just asking R to count the number of data points in each group so you don't need to specify this.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex))

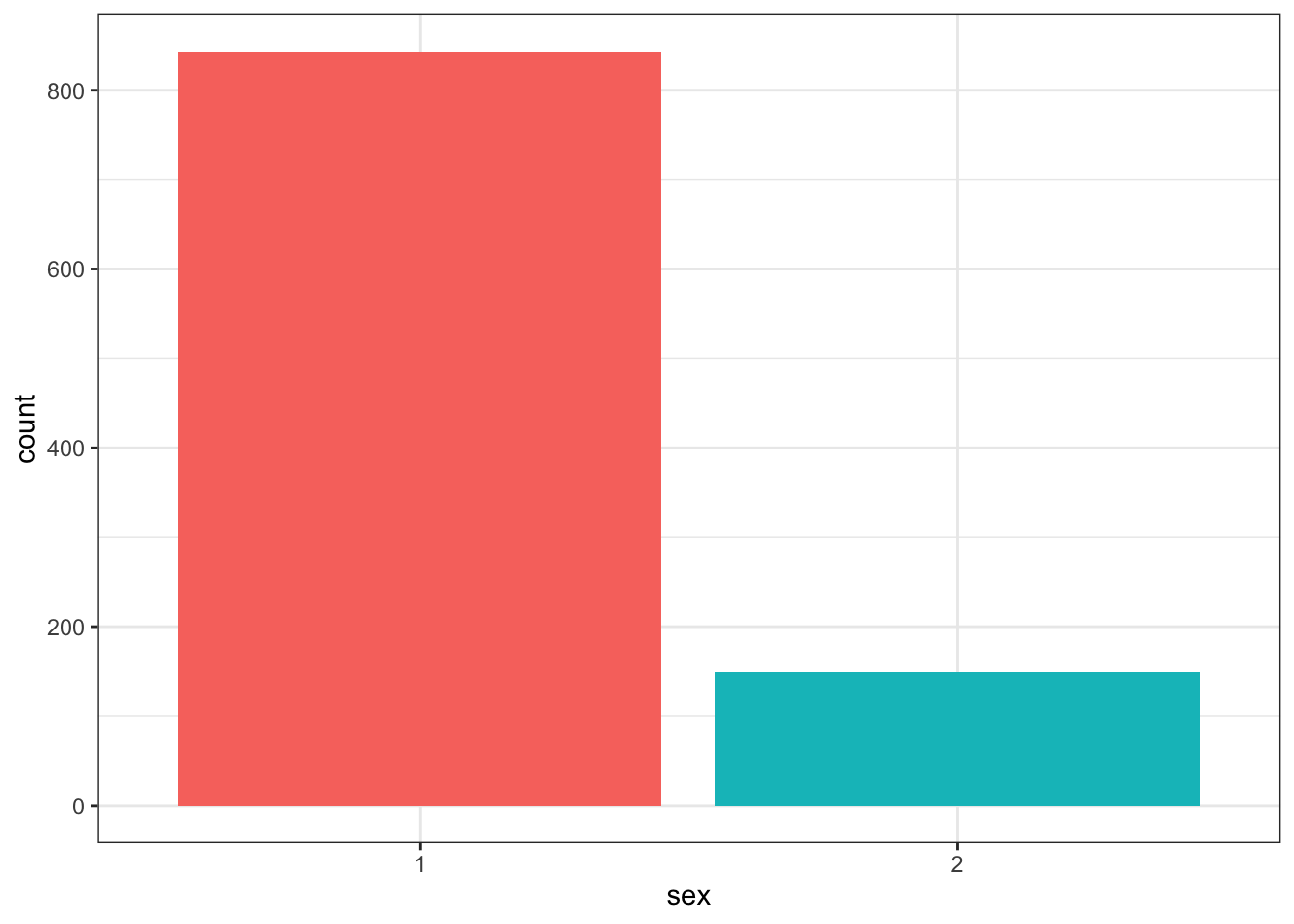

Figure 7.2: First ggplot layer sets the axes

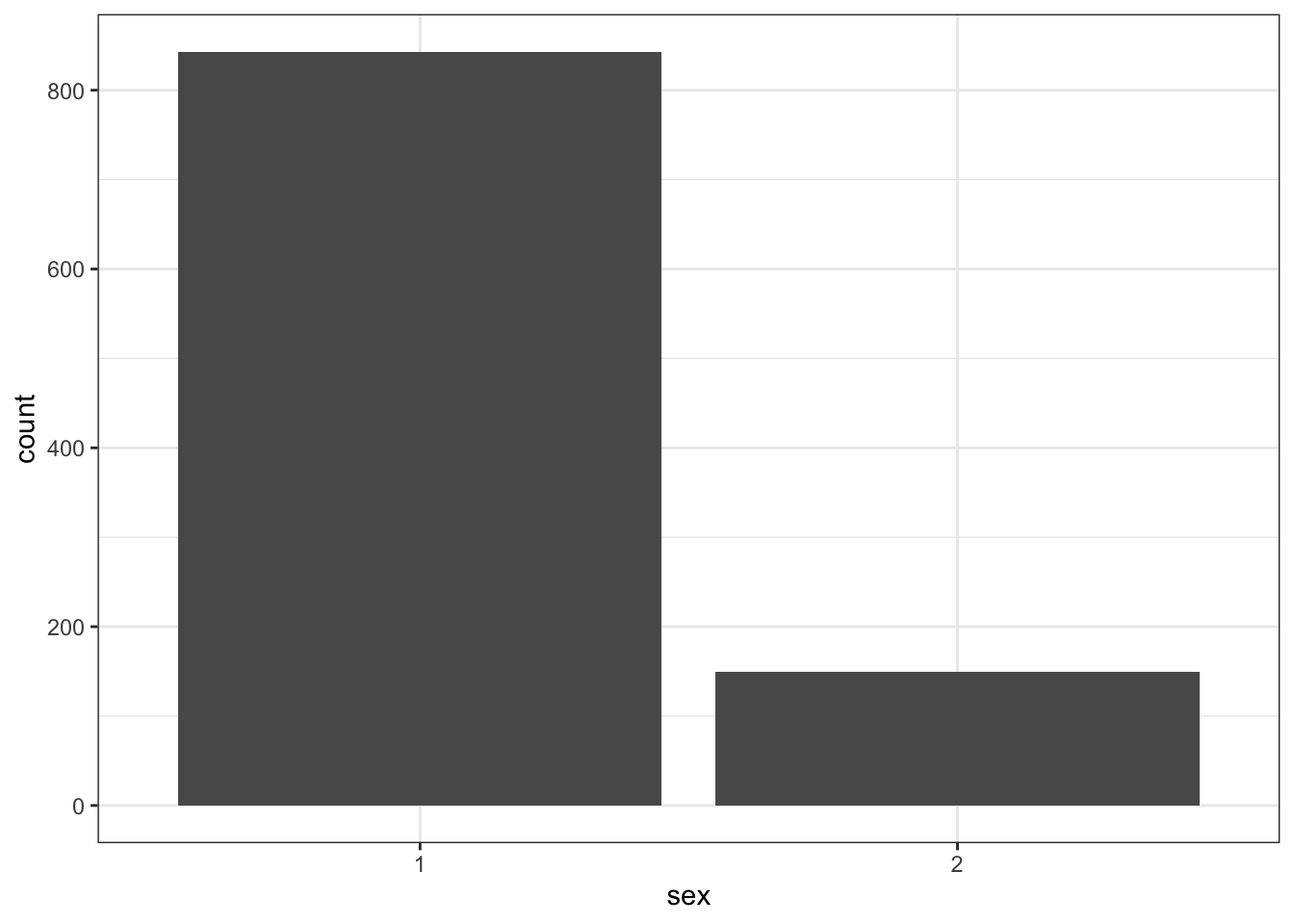

- The next layer adds a geom or a shape, in this case we use

geom_bar()as we want to draw a bar plot.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex)) +

geom_bar()

Figure 7.3: Basic barplot

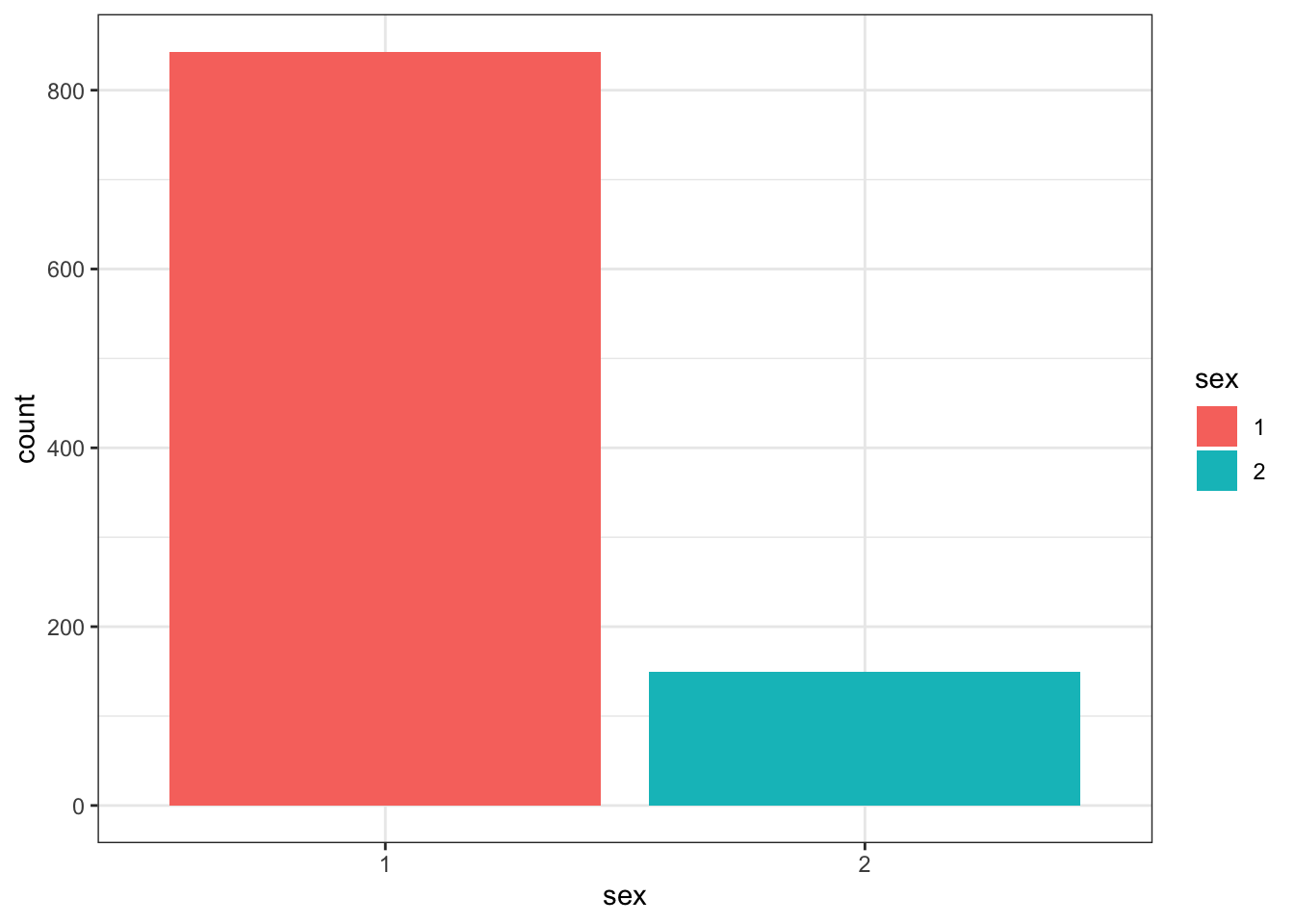

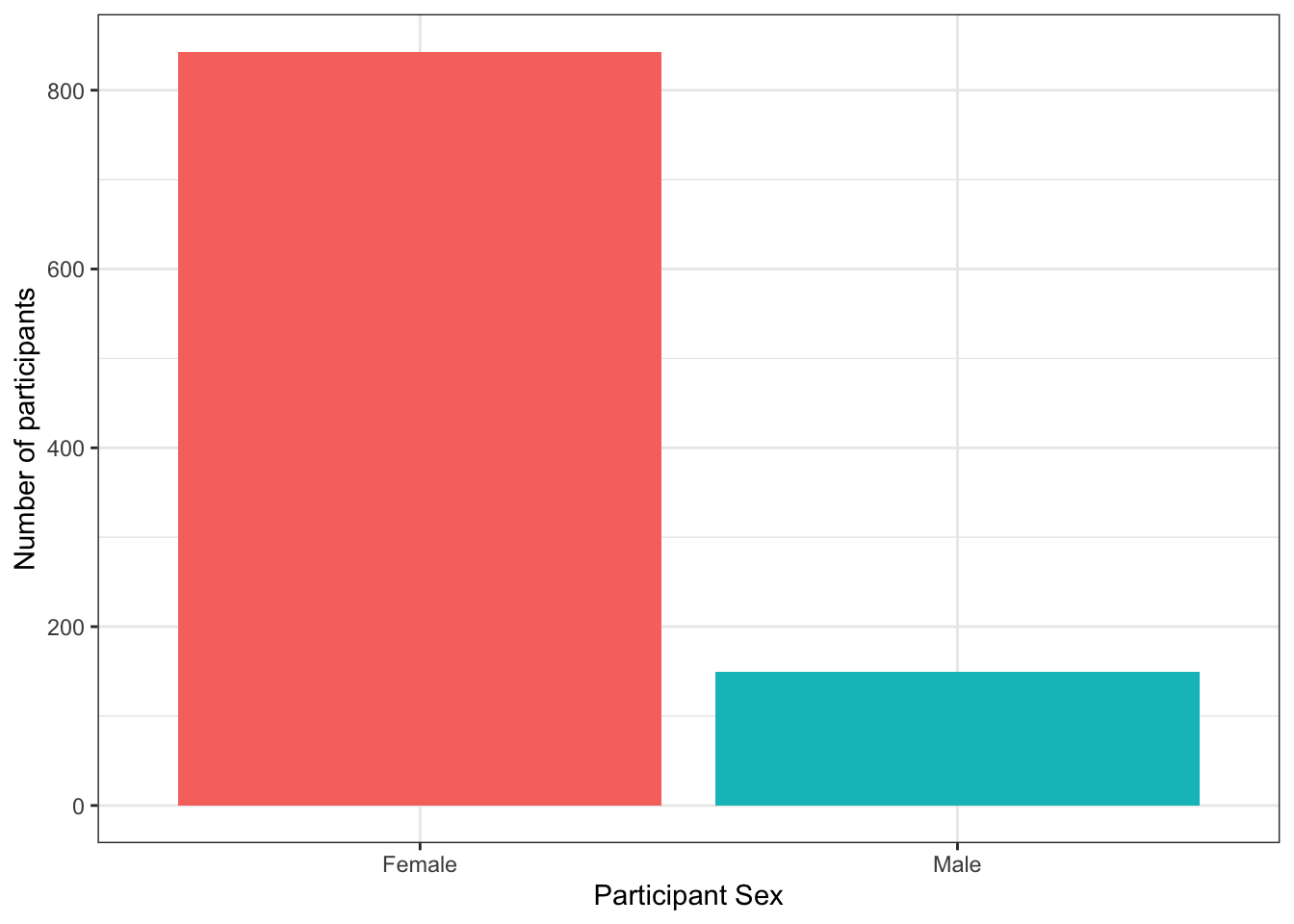

- Adding

fillto the first layer will separate the data into each level of the grouping variable and give it a different colour. In this case, there is a different coloured bar for each level ofsex.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar()

Figure 4.2: Barplot with colour

fill()has also produced a plot legend to the right of the graph. When you have multiple grouping variables you need this to know which groups each bit of the plot is referring to, but in this case it is redundant because it doesn't tell us anything that the axis labels don't already. We can get rid of it by addingshow.legend = FALSEto thegeom_bar()code.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar(show.legend = FALSE)

Figure 4.3: Barplot without legend

We might want to tidy up our plot to make it look a bit nicer. First we can edit the axis labels to be more informative. The most common functions you will use are:

scale_x_continuous()for adjusting the x-axis for a continuous variablescale_y_continuous()for adjusting the y-axis for a continuous variablescale_x_discrete()for adjusting the x-axis for a discrete/categorical variablescale_y_discrete()for adjusting the y-axis for a discrete/categorical variable

And in those functions the two most common arguments you will use are:

namewhich controls the name of each axislabelswhich controls the names of the break points on the axis

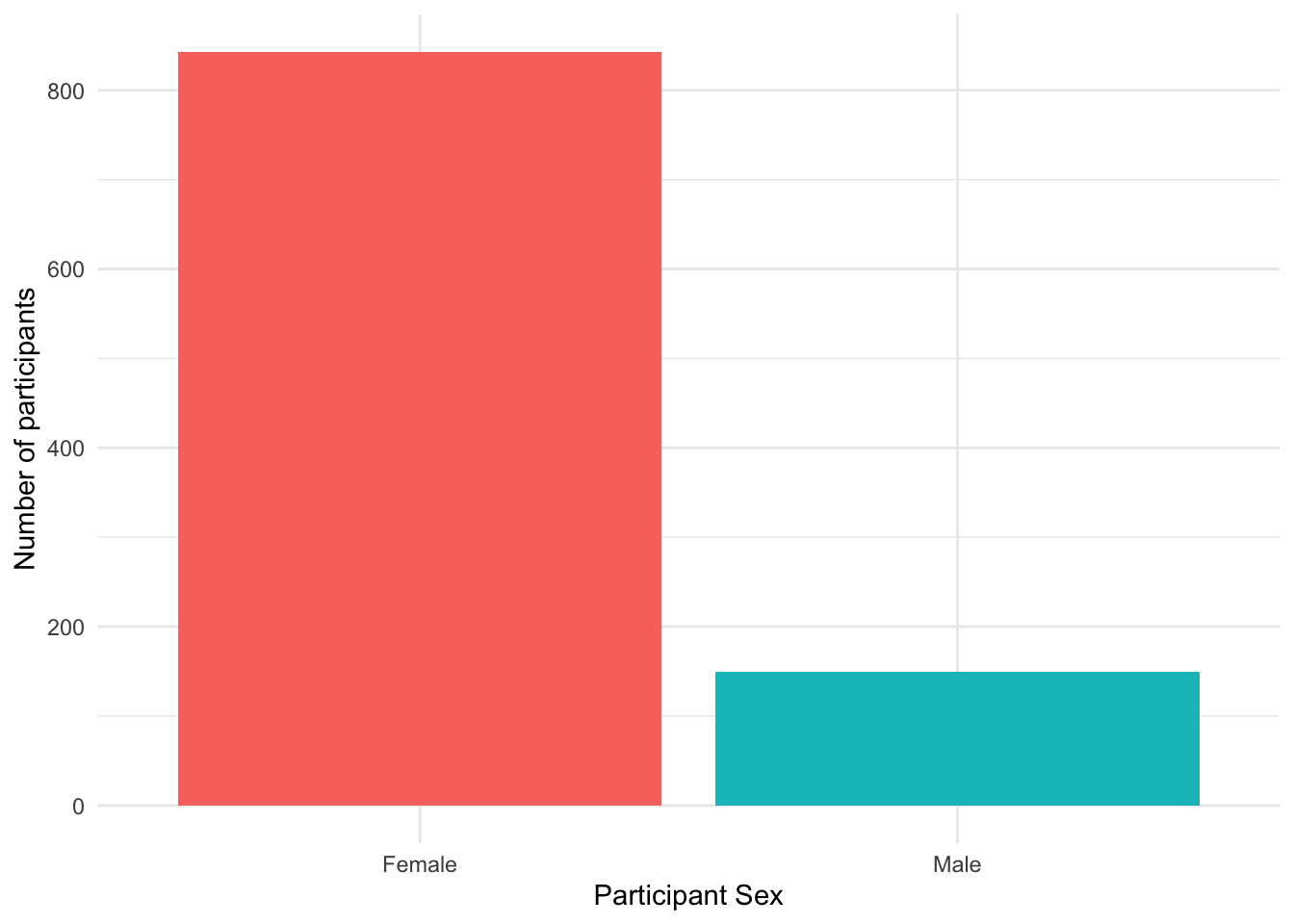

There are lots more ways you can customise your axes but we'll stick with these for now. Copy, paste, and run the below code to change the axis labels and change the numeric sex codes into words.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar(show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Participant Sex",

labels = c("Female", "Male")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Number of participants")

Figure 7.4: Barplot with axis labels

Second, you might want to adjust the colours and the visual style of the plot. ggplot2 comes with built in themes. Below, we'll use theme_minimal() but try typing theme_ into a code chunk and try all the options that come up to see which one you like best.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar(show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Participant Sex",

labels = c("Female", "Male")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Number of participants") +

theme_minimal()

Figure 7.5: Barplot with minimal theme

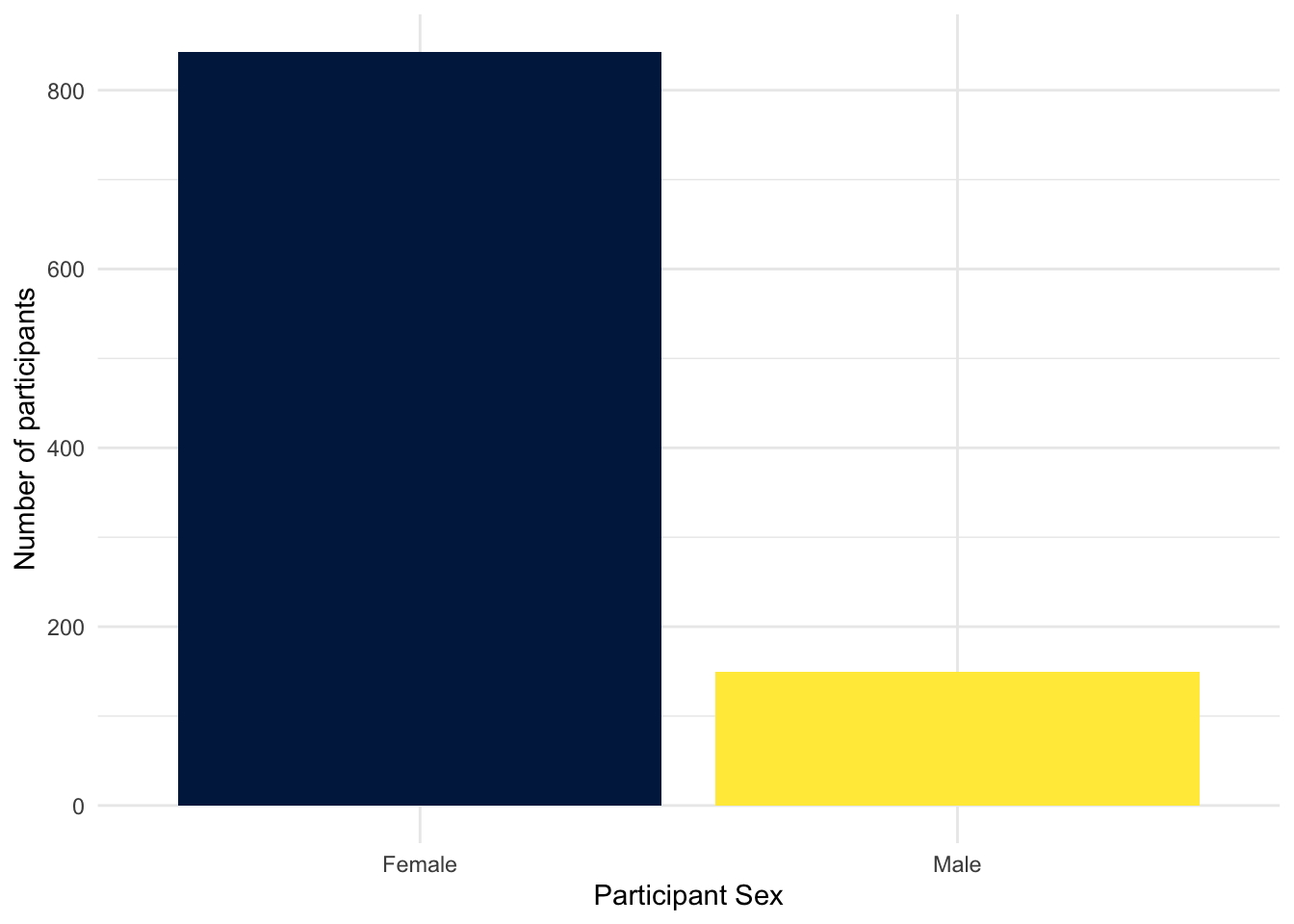

There are various options to adjust the colours but a good way to be inclusive is to use a colour-blind friendly palette that can also be read if printed in black-and-white. To do this, we can add on the function scale_fill_viridis_d(). This function has 5 colour options, A, B, C, D, and E. I prefer E but you can play around with them and choose the one you prefer.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar(show.legend = FALSE) +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Participant Sex",

labels = c("Female", "Male")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Number of participants") +

theme_minimal() +

scale_fill_viridis_d(option = "E")

Figure 7.6: Barplot with colour-blind friendly colour scheme

Finally, you can also adjust the transparency of the bars by adding alpha to geom_bar(). Play around with the value and see what value you prefer.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = sex, fill = sex)) +

geom_bar(show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .8) +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Participant Sex",

labels = c("Female", "Male")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Number of participants") +

theme_minimal() +

scale_fill_viridis_d(option = "E")

Figure 7.7: Barplot with adjusted alpha

In R terms, ggplot2 is a fairly old package. As a result, the use of pipes wasn't included when it was originally written. As you can see in the code above, the layers of the code are separated by + rather than %>%. In this case, + is doing essentially the same job as a pipe - be careful not to confuse them.

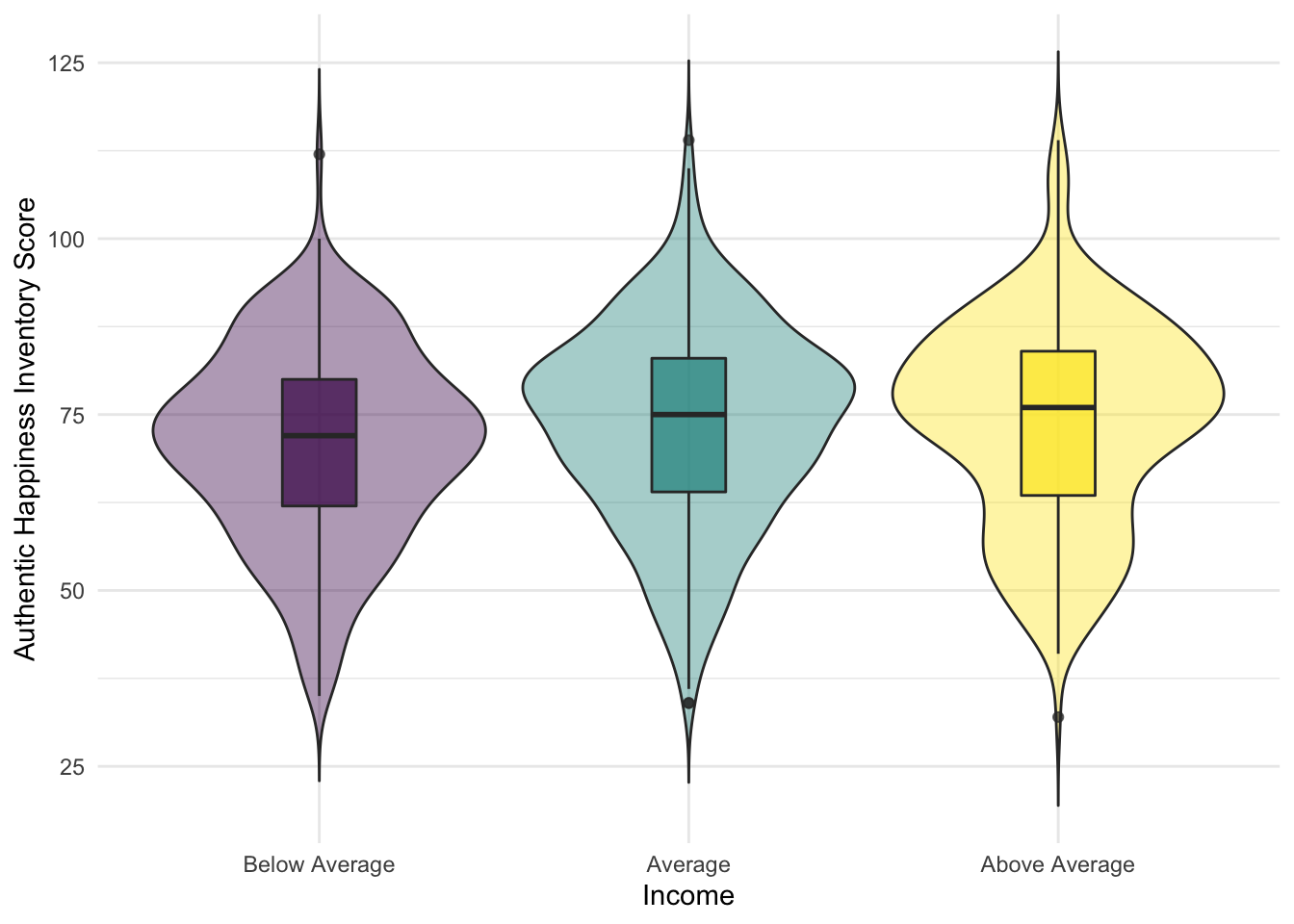

7.5 Activity 5: Violin-boxplot

As our final activity we will create a violin-boxplot, hopefully now you will be able to see how similar it is in structure to the bar chart code. In fact, there are only three differences:

- We have added a

yargument to the first layer because we wanted to represent two variables, not just a count. geom_violin()has an additional argumenttrim. Try setting this toTRUEto see what happens.geom_boxpot()has an additional argumentwidth. Try adjusting the value of this and see what happens.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = income, y = ahiTotal, fill = income)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .4) +

geom_boxplot(width = .2, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .7)+

scale_x_discrete(name = "Income",

labels = c("Below Average", "Average", "Above Average")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Authentic Happiness Inventory Score")+

theme_minimal() +

scale_fill_viridis_d()

Figure 7.8: Violin-boxplot

7.6 Activity 6: Layers part 2

The key thing to note about ggplot is the use of layers. Whilst we've built this up step-by-step, they are independent and you could remove any of them except for the first layer. Additionally, although they are independent, the order you put them in does matter. Try running the two code examples below and see what happens.

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = income, y = ahiTotal)) +

geom_violin() +

geom_boxplot()

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = income, y = ahiTotal)) +

geom_boxplot() +

geom_violin()7.7 Activity 7: Daving plots (#introviz-a7)

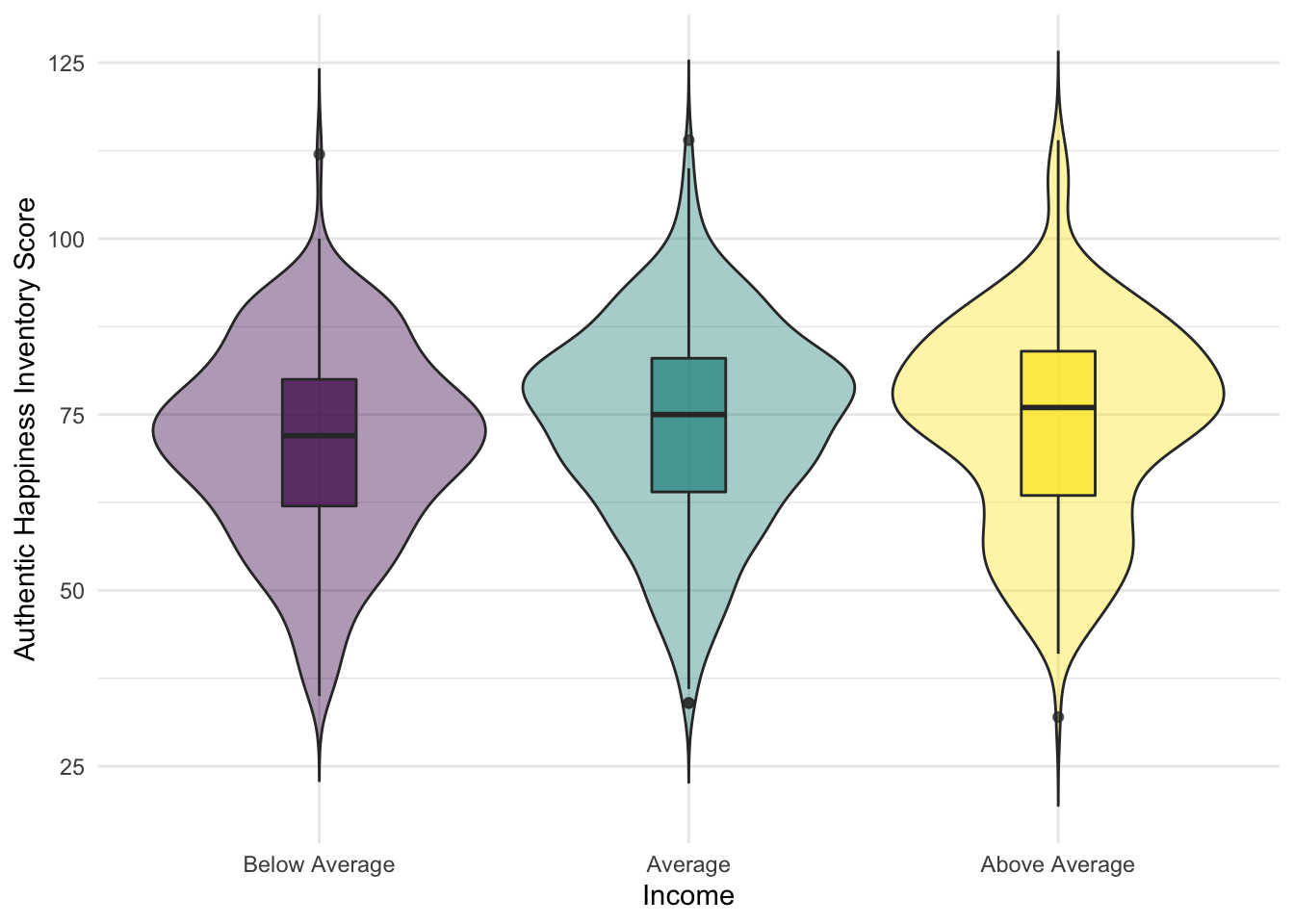

Finally, it's useful to be able to save a copy of your plots as an image file so that you can use it in a presentation or word document and to do this we can use the function ggsave().

There are two ways you can use ggsave(). If you don't tell ggsave() which plot you want to save, by default it will save a copy of the last plot you created. If you've been following this chapter in order, the last plot you created will have been the messy violin plot in Activity 6, so let's run the code from Activity 5 again tp produce the nice violin-boxplot:

ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = income, y = ahiTotal, fill = income)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .4) +

geom_boxplot(width = .2, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .7)+

scale_x_discrete(name = "Income",

labels = c("Below Average", "Average", "Above Average")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Authentic Happiness Inventory Score")+

theme_minimal() +

scale_fill_viridis_d()

Figure 7.9: Violin-boxplot2

Now that we've got the plot we want to save as our last produced plot, all that ggsave() requires is for you to tell it what file name it should save the plot to and the type of image file you want to create (the below example uses .png but you could also use e.g., .jpeg and other image types).

- Copy, paste and run the below code into a new code chunk.

- Check your chapter folder, you should now see the saved image file.

ggsave("violin-boxplot.png")The default size for an image is 7 x 7, you can change this manually if you think that the dimensions of the plot are not correct or if you need a particular size.

- Copy paste and run the below code to overwrite the image file with new dimensions.

ggsave("violin-boxplot", width = 10, height = 8)The second way of using ggsave() is to save your plot as an object and then tell it which object to write to a file. The below code saves the pipe plot from Activity 5 into an object named viobox and then saves it to an image file "violin-boxplot.png".

Note that when you save a plot to an object, it won't display in R Studio. To get it to display you need to type the object name in the console (i.e., viobox). The benefit of doing it this way is that if you are making lots of plots, you can't accidentally save the wrong one because you are explicitly specifying which plot to save rather than just saving the last one.

- Copy, paste and run the below code and then check your Data Skills folder for the image file. Resize the plot if you think it needs it.

viobox <- ggplot(summarydata, aes(x = income, y = ahiTotal, fill = income)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .4) +

geom_boxplot(width = .2, show.legend = FALSE, alpha = .7)+

scale_x_discrete(name = "Income",

labels = c("Below Average", "Average", "Above Average")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Authentic Happiness Inventory Score")+

theme_minimal() +

scale_fill_viridis_d()

ggsave("violin-boxplot.png", plot = viobox)7.7.1 Finished!

Well done! ggplot can be a bit difficult to get your head around at first, particularly if you've been used to making graphs a different way. But once it clicks, you'll be able to make informative and professional visualisations with ease, which, amongst other things, will make your reports look FANCY.