4 Working with Data

4.1 Learning Objectives

- Be able to structure data for scripting

- Load built-in datasets (video)

- Import data from CSV and Excel files (video)

- Create a data table (video)

- Understand and use the basic data types (video)

- Understand and use the basic container types (list, vector) (video)

- Use vectorized operations (video)

- Be able to troubleshoot common data import problems (video)

This chapter has a lot of jargon. Becoming familiar with these terms can help you to ask questions more clearly and search for answers online. Keywords are shown in purple; you can view a short definition by hovering over them and access a more detailed definition by clicking on them. All of the defined words are in the glossary at the end of this chapter.

4.2 Setup

- Open your

reprores-class-notesproject - Create a new R Markdown file called

04-data.Rmd - Update the YAML header

- Replace the setup chunk with the one below:

```{r setup, include = FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE)

# packages needed for this chapter

library(tidyverse) # loads readr for importing data

# and tibble for creating tables

library(readxl) # importing excel files

library(googlesheets4) # importing google sheets

library(haven) # importing SPSS files

library(jsonlite) # importing JSON files

library(rio) # importing and exporting many types of files

library(skimr) # summarising datasets

library(reprores) # class-specific datasets```Download the Data import cheatsheet.

4.3 Data structure

You're probably most familiar with data recorded in Excel spreadsheets. These are fine for data entry, but are very prone to error if used for calculations and analysis (see these horror stories). Broman & Woo (2018) recommend following several guidelines for less error-prone use of spreadsheets. The paper is well worth reading, but I'll summarise some of the most important guidelines here.

4.3.1 Be consistent

Use the same names for columns in different data files, and the exact same format for categorical values. Capitalisation and spaces also matter. For example, do not record group as "A", "a", and "A " in different places (or in the same column); these will be treated by any computational script as three different values.

If you have column names for items you might want to group later, such as a questionnaire with items belonging to one of three subscales, use a consistent naming convention. This will make it easier to reshape data to create subscale scores, which we will cover in Chapter 6.4. For example, use column names like O_1, E_2, O_3, C_4 rather than q1, q2, q3, q4. (Alternatively, you can include a separate table with a column for question number and a corresponding column for the subscale and join it to the reformatted questionnaire data, as we'll learn in Chapter 5.)

4.3.2 Choose good names for things

We covered this in Chapter 2.4.3 for file names. It is also important to use names for variables and values that make it easy to work with them in R. For example, use column names with only letters, numbers, full stops and underscores so you don't have to quote them. Using camel case is OK, just use a consistent naming scheme so you don't have to keep looking up whether you named a column SleepTime, sleepTime, sleep_time or sleep.time.

Choose the best consistent column names for a single data file:

4.3.3 Write dates as YYYY-MM-DD

This format is nearly impossible to misinterpret (unlike formats like "01/02/03") and sorts in a sensible order (unlike "January 2, 2003" or "2-1-03").

4.3.4 No empty cells

I'm not as strict about this one, but I do think that missing values should be either empty cells ("") or NA and that this should be consistent across all your data sets. If you use other values, this requires some extra steps at data import (see Section 4.4.2.3 below).

4.3.5 Put just one thing in a cell

Don't put two pieces of information in the same cell. For example, rather than a column called id-group containing subject ID and experimental group (e.g., "001A"), record this info in two columns, id and group. We'll learn more about tidy data in Chapter 6.

4.3.6 Make it a rectangle

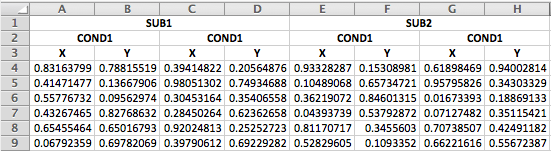

While merging cells or putting extra info into cells in a spreadsheet can look nice, it's a nightmare for data import.

Figure 4.1: Data with multiple headers and merged cells can take many extra steps to import.

We'll learn more about data formats to better represent data like this in Chapter 6. See this blog post for some solutions to deal with data like above.

4.3.7 Create a data dictionary

You may think all of your column names and factor labels are intuitive, but other researchers and future you will thank you for creating a data dictionary.

You can create a data dictionary manually, or use an R package to help you make them for data you've imported to R. Crystal Lewis reviews some of these, like codebookr.

4.3.9 Do not use font colour or highlighting

There are ways to extract this computationally, but they're complex and annoying to deal with. When you are tempted to use colour to highlight something like outliers, add a column with TRUE/FALSE or text values instead.

Find a paper in Psychological Science or another journal that encourages data sharing. Find a paper you're interested in that shares data (usually has this badge  ) and download the data (usually listed in the "Open Practices" section at the end). Access their data and assess how well they follow each of the guidelines above.

) and download the data (usually listed in the "Open Practices" section at the end). Access their data and assess how well they follow each of the guidelines above.

4.4 Data tables

4.4.1 Built-in data

R comes with built-in datasets. Some packages, like tidyr and reprores, also contain data. The data() function lists the datasets available in a package.

# lists datasets in reprores

data(package = "reprores")Type the name of a dataset into the console to see the data. Type ?smalldata into the console to see the dataset description.

smalldata| id | group | pre | post |

|---|---|---|---|

| S01 | control | 98.46606 | 106.70508 |

| S02 | control | 104.39774 | 89.09030 |

| S03 | control | 105.13377 | 123.67230 |

| S04 | control | 92.42574 | 70.70178 |

| S05 | control | 123.53268 | 124.95526 |

| S06 | exp | 97.48676 | 101.61697 |

| S07 | exp | 87.75594 | 126.30077 |

| S08 | exp | 77.15375 | 72.31229 |

| S09 | exp | 97.00283 | 108.80713 |

| S10 | exp | 102.32338 | 113.74732 |

You can also use the data() function to load a dataset into your global environment.

# loads smalldata into the environment

data("smalldata")Always, always, always, look at your data once you've created or loaded a table. Also look at it after each step that transforms your table. There are three main ways to look at your tibble: print(), glimpse(), and View().

The print() method can be run explicitly, but is more commonly called by just typing the variable name on the blank line. The default is not to print the entire table, but just the first 10 rows. It's rare to print your data in a script; that is something you usually are doing for a sanity check, and you should just do it in the console.

Let's look at the smalldata table that we made above.

smalldata| id | group | pre | post |

|---|---|---|---|

| S01 | control | 98.46606 | 106.70508 |

| S02 | control | 104.39774 | 89.09030 |

| S03 | control | 105.13377 | 123.67230 |

| S04 | control | 92.42574 | 70.70178 |

| S05 | control | 123.53268 | 124.95526 |

| S06 | exp | 97.48676 | 101.61697 |

| S07 | exp | 87.75594 | 126.30077 |

| S08 | exp | 77.15375 | 72.31229 |

| S09 | exp | 97.00283 | 108.80713 |

| S10 | exp | 102.32338 | 113.74732 |

The function glimpse() gives a sideways version of the tibble. This is useful if the table is very wide and you can't see all of the columns. It also tells you the data type of each column in angled brackets after each column name. We'll learn about data types below.

glimpse(smalldata)## Rows: 10

## Columns: 4

## $ id <chr> "S01", "S02", "S03", "S04", "S05", "S06", "S07", "S08", "S09", "…

## $ group <chr> "control", "control", "control", "control", "control", "exp", "e…

## $ pre <dbl> 98.46606, 104.39774, 105.13377, 92.42574, 123.53268, 97.48676, 8…

## $ post <dbl> 106.70508, 89.09030, 123.67230, 70.70178, 124.95526, 101.61697, …The other way to look at the table is a more graphical spreadsheet-like version given by View() (capital 'V'). It can be useful in the console, but don't ever put this one in a script because it will create an annoying pop-up window when the user runs it.

Now you can click on smalldata in the environment pane to open it up in a viewer that looks a bit like Excel.

You can get a quick summary of a dataset with the summary() function.

summary(smalldata)## id group pre post

## Length:10 Length:10 Min. : 77.15 Min. : 70.70

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.: 93.57 1st Qu.: 92.22

## Mode :character Mode :character Median : 97.98 Median :107.76

## Mean : 98.57 Mean :103.79

## 3rd Qu.:103.88 3rd Qu.:121.19

## Max. :123.53 Max. :126.30You can even do things like calculate the difference between the means of two columns.

## [1] 5.2230554.4.2 Importing data

Built-in data are nice for examples, but you're probably more interested in your own data. There are many different types of files that you might work with when doing data analysis. These different file types are usually distinguished by the three letter extension following a period at the end of the file name. Here are some examples of different types of files and the functions you would use to read them in or write them out.

| Extension | File Type | Reading | Writing |

|---|---|---|---|

| .csv | Comma-separated values | readr::read_csv() |

readr::write_csv() |

| .tsv, .txt | Tab-separated values | readr::read_tsv() |

readr::write_tsv() |

| .xls, .xlsx | Excel workbook | readxl::read_excel() |

rio::export() |

| .sav | SPSS files | haven::read_sav() |

haven::write_sav() |

| .json | JSON files | jsonlite::read_json() |

jsonlite::write_json() |

| .mat, ... | Multiple types | rio::import() |

rio::export() |

The double colon means that the function on the right comes from the package on the left, so readr::read_csv() refers to the read_csv() function in the readr package, and readxl::read_excel() refers to the function read_excel() in the readxl package. The function rio::import() from the rio package will read almost any type of data file, including SPSS and Matlab. Check the help with ?rio::import to see a full list.

You can get a directory of data files used in this class for tutorials and exercises with the following code, which will create a directory called "data" in your project directory. Alternatively, you can download a zip file of the datasets.

reprores::getdata()4.4.2.1 CSV Files

The most common file type you will encounter in this class is .csv (comma-separated values). As the name suggests, a CSV file distinguishes which values go with which variable by separating them with commas, and text values are sometimes enclosed in double quotes. The first line of a file usually provides the names of the variables.

For example, here is a small CSV containing demo data:

```

character,integer,double,logical,date

A,1,1.5,TRUE,05-Sep-21

B,2,2.5,TRUE,04-Sep-21

C,3,3.5,FALSE,03-Sep-21

D,4,4.5,FALSE,02-Sep-21

E,5,5.5,,01-Sep-21

F,6,6.5,TRUE,31-Aug-21

```There are five variables in this dataset, and their names are given in the first line of the file: character, integer, double ,`logical, and date. You can see that the values for each of these variables are given in order, separated by commas, on each subsequent line of the file.

Use readr::read_csv() to read in the data as assign it to an object called demo_csv.

demo_csv <- readr::read_csv("data/demo.csv")## Rows: 6 Columns: 5

## ── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

## Delimiter: ","

## chr (2): character, date

## dbl (2): integer, double

## lgl (1): logical

##

## ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

## ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.This function will give you some information about the data you just read in so you can check the column names and data types. If it makes a mistake, such as reading the "date" column as a character, you can manually set the column data types. Just copy the "Column specification" that was printed when you first imported the data, and make any changes you need.

ct <- cols(

character = col_character(),

integer = col_double(),

double = col_double(),

logical = col_logical(),

date = col_date(format = "%d-%b-%y")

)

demo <- readr::read_csv("data/demo.csv", col_types = ct)For dates, you might need to set the format. See ?strptime for a list of the codes used to represent different date formats. Above, "%d-%b-%y" means that the dates are formatted like {day number}-{month abbreviation}-{2-digit year}.

We'll learn more about how to fix data import problems in the troubleshooting section below.

4.4.2.2 Other File Types

Use the functions below to read in other file types.

demo_tsv <- readr::read_tsv("data/demo.tsv")

demo_xls <- readxl::read_excel("data/demo.xlsx")

demo_sav <- haven::read_sav("data/demo.sav")

demo_json <- jsonlite::read_json("data/demo.json")You can access Google Sheets directly from R using googlesheets4.

googlesheets4::gs4_deauth() # skip authorisation for public data

url <- "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16dkq0YL0J7fyAwT1pdgj1bNNrheckAU_2-DKuuM6aGI/"

demo_goo <- googlesheets4::read_sheet(url)Try loading in all five of the 5factor datasets in the data directory.

ocean_csv <- readr::read_csv("data/5factor.csv")

ocean_tsv <- readr::read_tsv("data/5factor.txt")

ocean_xls <- readxl::read_excel("data/5factor.xls")

ocean_xlsx <- readxl::read_excel("data/5factor.xlsx")

ocean_sav <- haven::read_sav("data/5factor.sav")4.4.2.3 Missing Values

If you represent missing values with anything other than a blank cell or "NA", you need to specify this. Set the argument na to a vector of all the values that are used to represent missing data. By default this is set to c("", "NA"), so you will also need to change it if you have valid values that really are the word "NA", such as the 2-letter ISO country code for Nigeria.

# make a short CSV string with two types of missing values

csv_text <- "id, country

1, UK

2, missing

3,

4, NA"

readr::read_csv(csv_text, na = c("", "missing"),

show_col_types = FALSE)| id | country |

|---|---|

| 1 | UK |

| 2 | NA |

| 3 | NA |

| 4 | NA |

4.4.3 Inspecting data

Now that you've loaded some data, look the upper right hand window of RStudio, under the Environment tab. You will see the objects listed, along with their number of observations (rows) and variables (columns). This is your first check that everything went OK.

Always, always, always, inspect your data once you've created or loaded a table and after each step that transforms your table. The quickest and most basic way is to look at your table using View() or print(). You can also use functions like tibble::glimpse(), summary() or skimr::skim() to summarise your data. Finally, the best way to really understand your data is to plot it using the skills we learned in Chapter 3.

4.4.3.1 Viewing data

A familiar way to look at the table is given by View() (uppercase 'V'). This command can be useful in the console, but don't ever put this one in a script because it will create an annoying pop-up window when the user runs it. Or you can click on an objects in the environment pane to open it up in a viewer that looks a bit like Excel. You can close the tab when you're done looking at it; it won't remove the object.

The print() method can be run explicitly, but is more commonly called by just typing the variable name on the blank line. The default is not to print the entire table, but just the first 10 rows.

Let's look at the demo_tsv table that we loaded above. Depending on how wide your screen is, you might need to click on an arrow at the right of the table to see the last column.

demo_tsv| character | integer | double | logical | date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 1.5 | TRUE | 05-Sep-21 |

| B | 2 | 2.5 | TRUE | 04-Sep-21 |

| C | 3 | 3.5 | FALSE | 03-Sep-21 |

| D | 4 | 4.5 | FALSE | 02-Sep-21 |

| E | 5 | 5.5 | NA | 01-Sep-21 |

| F | 6 | 6.5 | TRUE | 31-Aug-21 |

Remember that the way tables are displayed can look different in the interactive interface from the knit version, depending on how df_print is set.

4.4.3.2 Summarising data

The function tibble::glimpse() gives a sideways version of the table. This is useful if the table is very wide and you can't see all of the columns. It also tells you the data type of each column in angled brackets after each column name.

glimpse(demo_xls)## Rows: 6

## Columns: 5

## $ character <chr> "A", "B", "C", "D", "E", "F"

## $ integer <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

## $ double <dbl> 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5

## $ logical <lgl> TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, NA, TRUE

## $ date <chr> "05-Sep-21", "04-Sep-21", "03-Sep-21", "02-Sep-21", "01-Sep-…You can get a quick summary of a dataset with the summary() function.

summary(demo_sav)## character integer double logical

## Length:6 Min. :1.00 Min. :1.50 Min. :0.0

## Class :character 1st Qu.:2.25 1st Qu.:2.75 1st Qu.:0.0

## Mode :character Median :3.50 Median :4.00 Median :1.0

## Mean :3.50 Mean :4.00 Mean :0.6

## 3rd Qu.:4.75 3rd Qu.:5.25 3rd Qu.:1.0

## Max. :6.00 Max. :6.50 Max. :1.0

## NA's :1

## date

## Length:6

## Class :character

## Mode :character

##

##

##

## There are other packages that can give you a more detailed summary, such as skimr.

skimr::skim(demo)| Name | demo |

| Number of rows | 6 |

| Number of columns | 5 |

| _______________________ | |

| Column type frequency: | |

| character | 1 |

| Date | 1 |

| logical | 1 |

| numeric | 2 |

| ________________________ | |

| Group variables | None |

Variable type: character

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | min | max | empty | n_unique | whitespace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| character | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

Variable type: Date

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | min | max | median | n_unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| date | 0 | 1 | 2021-08-31 | 2021-09-05 | 2021-09-02 | 6 |

Variable type: logical

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| logical | 1 | 0.83 | 0.6 | TRU: 3, FAL: 2 |

Variable type: numeric

| skim_variable | n_missing | complete_rate | mean | sd | p0 | p25 | p50 | p75 | p100 | hist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| integer | 0 | 1 | 3.5 | 1.87 | 1.0 | 2.25 | 3.5 | 4.75 | 6.0 | ▇▃▃▃▃ |

| double | 0 | 1 | 4.0 | 1.87 | 1.5 | 2.75 | 4.0 | 5.25 | 6.5 | ▇▃▃▃▃ |

4.4.4 Creating data

If we are creating a data table from scratch, we can use the tibble::tibble() function, and type the data right in. The tibble package is part of the tidyverse package that we loaded at the start of this chapter.

Let's create a small table with the names of three Avatar characters and their bending type. The tibble() function takes arguments with the names that you want your columns to have. The values are vectors that list the column values in order.

If you don't know the value for one of the cells, you can enter NA, which we have to do for Sokka because he doesn't have any bending ability. If all the values in the column are the same, you can just enter one value and it will be copied for each row.

avatar <- tibble(

name = c("Katara", "Toph", "Sokka"),

bends = c("water", "earth", NA),

friendly = TRUE

)

# print it

avatar| name | bends | friendly |

|---|---|---|

| Katara | water | TRUE |

| Toph | earth | TRUE |

| Sokka | NA | TRUE |

4.4.5 Writing Data

If you have data that you want to save to a CSV file, use readr::write_csv(), as follows.

write_csv(avatar, "avatar.csv")This will save the data in CSV format to your working directory.

Writing to Google Sheets is a little trickier. Even if a Google Sheet is publicly editable, you can't add data to it without authorising your account.

You can authorise interactively using the following code (and your own email), which will prompt you to authorise "Tidyverse API Packages" the first time you do this.

gs4_auth(email = "debruine@gmail.com")

sheet_id <- gs4_create("demo-file", sheets = demo)

new_data <- tibble(

character = "Z",

integer = 0L,

double = 0.5,

logical = FALSE,

date = "01-Jan-00"

)

sheet_append(sheet_id, new_data)

demo <- read_sheet(sheet_id)- Create a new table called

familywith the first name, last name, and age of your family members. - Save it to a CSV file called

family.csv. - Clear the object from your environment by restarting R or with the code

remove(family). - Load the data back in and view it.

We'll be working with tabular data a lot in this class, but tabular data is made up of vectors, which group together data with the same basic data type. The following sections explain some of this terminology to help you understand the functions we'll be learning to process and analyse data.

4.5 Basic data types

Data can be numbers, words, true/false values or combinations of these. The basic data types in R are: numeric, character, and logical, as well as the special classes of factor and date/times.

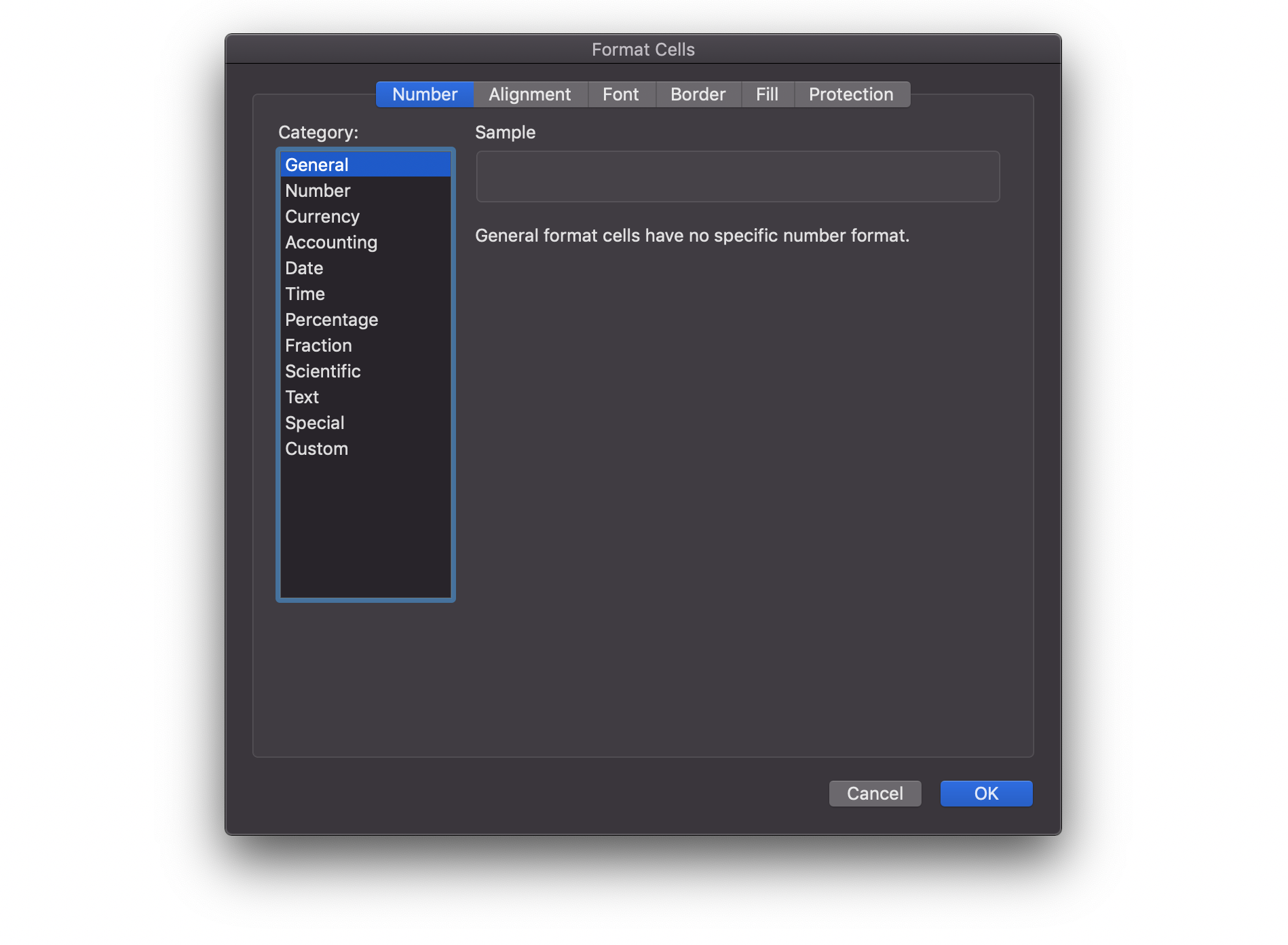

Figure 4.2: Data types are like the categories when you format cells in Excel.

4.5.1 Numeric data

All of the real numbers are numeric data types (imaginary numbers are "complex"). There are two types of numeric data, integer and double. Integers are the whole numbers, like -1, 0 and 1. Doubles are numbers that can have fractional amounts. If you just type a plain number such as 10, it is stored as a double, even if it doesn't have a decimal point. If you want it to be an exact integer, use the L suffix (10L).

If you ever want to know the data type of something, use the typeof() function.

## [1] "double"

## [1] "double"

## [1] "integer"

## [1] "complex"If you want to know if something is numeric (a double or an integer), you can use the function is.numeric() and it will tell you if it is numeric (TRUE) or not (FALSE).

is.numeric(10L)

is.numeric(10.0)

is.numeric("Not a number")## [1] TRUE

## [1] TRUE

## [1] FALSE4.5.2 Character data

Characters (also called "strings") are any text between quotation marks.

## [1] "character"

## [1] "character"This can include quotes, but you have to escape it using a backslash to signal the the quote isn't meant to be the end of the string.

my_string <- "The instructor said, \"R is cool,\" and the class agreed."

cat(my_string) # cat() prints the arguments## The instructor said, "R is cool," and the class agreed.4.5.3 Logical Data

Logical data (also sometimes called "boolean" values) is one of two values: true or false. In R, we always write them in uppercase: TRUE and FALSE.

## [1] "logical"

## [1] "logical"You might also see logical values abbreviated as T and F, or 0 and 1. This can cause some problems down the road, so we will always spell out the whole thing.

R Markdown headers use YAML format, not R, so the logical values are lowercase true and false without quotes.

When you compare two values with an operator, such as checking to see if 10 is greater than 5, the resulting value is logical.

is.logical(10 > 5)## [1] TRUE4.5.4 Factors

A factor is a specific type of integer that lets you specify the categories and their order. This is useful in data tables to make plots display with categories in the correct order.

## [1] B

## Levels: A B CFactors are a type of integer, but you can tell that they are factors by checking their class().

## [1] "integer"

## [1] "factor"4.5.5 Dates and Times

Dates and times are represented by doubles with special classes. Although typeof() will tell you they are a double, you can tell that they are dates by checking their class(). Datetimes can have one or more of a few classes that start with POSIX.

date <- as.Date("2022-01-24")

datetime <- ISOdatetime(2022, 1, 24, 10, 35, 00, "GMT")

typeof(date)

typeof(datetime)

class(date)

class(datetime)## [1] "double"

## [1] "double"

## [1] "Date"

## [1] "POSIXct" "POSIXt"See Appendix G for how to use lubridate to work with dates and times.

What data types are these:

-

100 -

100L -

"100" -

100.0 -

-100L -

factor(100) -

TRUE -

"TRUE" -

FALSE -

1 == 2

4.6 Basic container types

Individual data values can be grouped together into containers. The main types of containers we'll work with are vectors, lists, and data tables.

4.6.1 Vectors

A vector in R is like a vector in mathematics: a set of ordered elements. All of the elements in a vector must be of the same data type (numeric, character, logical). You can create a vector by enclosing the elements in the function c().

## put information into a vector using c(...)

c(1, 2, 3, 4)

c("this", "is", "cool")

1:6 # shortcut to make a vector of all integers x:y## [1] 1 2 3 4

## [1] "this" "is" "cool"

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6What happens when you mix types? What class is the variable mixed?

mixed <- c(2, "good", 2L, "b", TRUE)

typeof(mixed)## [1] "character"You can't mix data types in a vector; all elements of the vector must be the same data type. If you mix them, R will "coerce" them so that they are all the same. If you mix doubles and integers, the integers will be changed to doubles. If you mix characters and numeric types, the numbers will be coerced to characters, so 10 would turn into "10".

4.6.1.1 Selecting values from a vector

If we wanted to pick specific values out of a vector by position, we can use square brackets (an extract operator, or []) after the vector.

values <- c(10, 20, 30, 40, 50)

values[2] # selects the second value## [1] 20You can select more than one value from the vector by putting a vector of numbers inside the square brackets. For example, you can select the 18th, 19th, 20th, 21st, 4th, 9th and 15th letter from the built-in vector LETTERS (which gives all the uppercase letters in the Latin alphabet).

word <- c(18, 19, 20, 21, 4, 9, 15)

LETTERS[word]## [1] "R" "S" "T" "U" "D" "I" "O"Can you decode the secret message?

secret <- c(14, 5, 22, 5, 18, 7, 15, 14, 14, 1, 7, 9, 22, 5, 25, 15, 21, 21, 16)You can also create 'named' vectors, where each element has a name. For example:

vec <- c(first = 77.9, second = -13.2, third = 100.1)

vec## first second third

## 77.9 -13.2 100.1We can then access elements by name using a character vector within the square brackets. We can put them in any order we want, and we can repeat elements:

vec[c("third", "second", "second")]## third second second

## 100.1 -13.2 -13.2We can get the vector of names using the names() function, and we can set or change them using something like names(vec2) <- c("n1", "n2", "n3").

Another way to access elements is by using a logical vector within the square brackets. This will pull out the elements of the vector for which the corresponding element of the logical vector is TRUE. If the logical vector doesn't have the same length as the original, it will repeat. You can find out how long a vector is using the length() function.

## [1] 26

## [1] "A" "C" "E" "G" "I" "K" "M" "O" "Q" "S" "U" "W" "Y"4.6.1.2 Repeating Sequences

Here are some useful tricks to save typing when creating vectors.

In the command x:y the : operator would give you the sequence of number starting at x, and going to y in increments of 1.

1:10

15.3:20.5

0:-10## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

## [1] 15.3 16.3 17.3 18.3 19.3 20.3

## [1] 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7 -8 -9 -10What if you want to create a sequence but with something other than integer steps? You can use the seq() function. Look at the examples below and work out what the arguments do.

## [1] -1.0 -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

## [1] 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

## [1] 0.0 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8 3.2 3.6 4.0 4.4 4.8 5.2 5.6

## [16] 6.0 6.4 6.8 7.2 7.6 8.0 8.4 8.8 9.2 9.6 10.0What if you want to repeat a vector many times? You could either type it out (painful) or use the rep() function, which can repeat vectors in different ways.

rep(0, 10) # ten zeroes

rep(c(1L, 3L), times = 7) # alternating 1 and 3, 7 times

rep(c("A", "B", "C"), each = 2) # A to C, 2 times each## [1] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

## [1] 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 3 1 3

## [1] "A" "A" "B" "B" "C" "C"The rep() function is useful to create a vector of logical values (TRUE/FALSE or 1/0) to select values from another vector.

# Get subject IDs in the pattern Y Y N N ...

subject_ids <- 1:40

yynn <- rep(c(TRUE, FALSE), each = 2,

length.out = length(subject_ids))

subject_ids[yynn]## [1] 1 2 5 6 9 10 13 14 17 18 21 22 25 26 29 30 33 34 37 384.6.1.3 Vectorized Operations

R performs calculations on vectors in a special way. Let's look at an example using \(z\)-scores. A \(z\)-score is a deviation score divided by a standard deviation. Let's say we have a set of four IQ scores.

## example IQ scores: mu = 100, sigma = 15

iq <- c(86, 101, 127, 99)If we want to subtract the mean from these four scores, we just use the following code:

iq - 100## [1] -14 1 27 -1This subtracts 100 from each element of the vector. R automatically assumes that this is what you wanted to do; it is called a vectorized operation and it makes it possible to express operations more efficiently.

To calculate \(z\)-scores we use the formula:

\(z = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma}\)

where X are the scores, \(\mu\) is the mean, and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation. We can expression this formula in R as follows:

## z-scores

(iq - 100) / 15## [1] -0.93333333 0.06666667 1.80000000 -0.06666667You can see that it computed all four \(z\)-scores with a single line of code. In later chapters, we'll use vectorised operations to process our data, such as reverse-scoring some questionnaire items.

4.6.2 Lists

Recall that vectors can contain data of only one type. What if you want to store a collection of data of different data types? For that purpose you would use a list. Define a list using the list() function.

data_types <- list(

double = 10.0,

integer = 10L,

character = "10",

logical = TRUE

)

str(data_types) # str() prints lists in a condensed format## List of 4

## $ double : num 10

## $ integer : int 10

## $ character: chr "10"

## $ logical : logi TRUEYou can refer to elements of a list using square brackets like a vector, but you can also use the dollar sign notation ($) if the list items have names.

data_types$logical## [1] TRUEExplore the 5 ways shown below to extract a value from a list. What data type is each object? What is the difference between the single and double brackets? Which one is the same as the dollar sign?

bracket1 <- data_types[1]

bracket2 <- data_types[[1]]

name1 <- data_types["double"]

name2 <- data_types[["double"]]

dollar <- data_types$doubleThe single brackets (bracket1 and name1) return a list with the subset of items inside the brackets. In this case, that's just one item, but can be more (try data_types[1:2]). The items keep their names if they have them, so the returned value is list(double = 10).

The double brackets (bracket2 and name2 return a single item as a vector. You can't select more than one item; data_types[[1:2]] will give you a "subscript out of bounds" error.

The dollar-sign notation is the same as double-brackets. If the name has spaces or any characters other than letters, numbers, underscores, and full stops, you need to surround the name with backticks (e.g., sales$`Customer ID`).

4.6.3 Tables

The built-in, imported, and created data above are tabular data, data arranged in the form of a table.

Tabular data structures allow for a collection of data of different types (characters, integers, logical, etc.) but subject to the constraint that each "column" of the table (element of the list) must have the same number of elements. The base R version of a table is called a data.frame, while the 'tidyverse' version is called a tibble. Tibbles are far easier to work with, so we'll be using those. To learn more about differences between these two data structures, see vignette("tibble").

Tabular data becomes especially important for when we talk about tidy data in chapter 4, which consists of a set of simple principles for structuring data.

4.6.3.1 Creating a table

We learned how to create a table by importing a CSV or Excel file, and creating a table from scratch using the tibble() function. You can also use the tibble::tribble() function to create a table by row, rather than by column. You start by listing the column names, each preceded by a tilde (~), then you list the values for each column, row by row, separated by commas (don't forget a comma at the end of each row). This method can be easier for some data, but doesn't let you use shortcuts, like setting all of the values in a column to the same value or a repeating sequence.

4.6.3.2 Table info

We can get information about the table using the functions:

-

ncol(): number of columns -

nrow(): number of rows -

dim(): the number of rows and number of columns -

name(): the column names -

glimpse(): the column types

## [1] 3

## [1] 3

## [1] 3 3

## [1] "name" "bends" "friendly"

## Rows: 3

## Columns: 3

## $ name <chr> "Katara", "Toph", "Sokka"

## $ bends <chr> "water", "earth", NA

## $ friendly <lgl> TRUE, TRUE, TRUE4.6.3.3 Accessing rows and columns

There are various ways of accessing specific columns or rows from a table. You'll be learning more about this in Chapters 6 and 7.

siblings <- avatar %>% slice(1, 3) # rows (by number)

bends <- avatar %>% pull(2) # column vector (by number)

friendly <- avatar %>% pull(friendly) # column vector (by name)

bends_name <- avatar %>% select(bends, name) # subset table (by name)

toph <- avatar %>% pull(name) %>% pluck(2) # single cellThe code below uses base R to produce the same subsets as the functions above. This format is useful to know about, since you might see them in other people's scripts.

4.7 Troubleshooting

What if you import some data and it guesses the wrong column type? The most common reason is that a numeric column has some non-numbers in it somewhere. Maybe someone wrote a note in an otherwise numeric column. Columns have to be all one data type, so if there are any characters, the whole column is converted to character strings, and numbers like 1.2 get represented as "1.2", which will cause very weird errors like "100" < "9" == TRUE. You can catch this by using glimpse() to check your data.

The data directory you created with reprores::getdata() contains a file called "mess.csv". Let's try loading this dataset.

# lazy = FALSE loads the data right away so you can see error messages

# this default changed in late 2021 and might change back soon

mess <- read_csv("data/mess.csv", lazy = FALSE)## Warning: One or more parsing issues, call `problems()` on your data frame for details,

## e.g.:

## dat <- vroom(...)

## problems(dat)## Rows: 27 Columns: 1

## ── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

## Delimiter: ","

## chr (1): This is my messy dataset

##

## ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

## ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.You'll get a warning with many parsing errors and the data table is just a single column. View the file data/mess.csv by clicking on it in the File pane, and choosing "View File". Here are the first 10 lines. What went wrong?

This is my messy dataset

junk,order,score,letter,good,min_max,date

junk,1,-1,a,1,1 - 2,2020-01-1

junk,missing,0.72,b,1,2 - 3,2020-01-2

junk,3,-0.62,c,FALSE,3 - 4,2020-01-3

junk,4,2.03,d,T,4 - 5,2020-01-4First, the file starts with a note: "This is my messy dataset". We want to skip the first two lines. You can do this with the argument skip in read_csv().

mess <- read_csv("data/mess.csv",

skip = 2,

lazy = FALSE)## Rows: 26 Columns: 7

## ── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

## Delimiter: ","

## chr (6): junk, order, letter, good, min_max, date

## dbl (1): score

##

## ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

## ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.

glimpse(mess)## Rows: 26

## Columns: 7

## $ junk <chr> "junk", "junk", "junk", "junk", "junk", "junk", "junk", "junk"…

## $ order <chr> "1", "missing", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", "9", "10", "11",…

## $ score <dbl> -1.00, 0.72, -0.62, 2.03, NA, 0.99, 0.03, 0.67, 0.57, 0.90, -1…

## $ letter <chr> "a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g", "h", "i", "j", "k", "l", "m…

## $ good <chr> "1", "1", "FALSE", "T", "1", "0", "T", "TRUE", "1", "T", "F", …

## $ min_max <chr> "1 - 2", "2 - 3", "3 - 4", "4 - 5", "5 - 6", "6 - 7", "7 - 8",…

## $ date <chr> "2020-01-1", "2020-01-2", "2020-01-3", "2020-01-4", "2020-01-5…OK, that's a little better, but this table is still a serious mess in several ways:

-

junkis a column that we don't need -

ordershould be an integer column -

goodshould be a logical column -

gooduses all kinds of different ways to record TRUE and FALSE values -

min_maxcontains two pieces of numeric information, but is a character column -

dateshould be a date column

We'll learn how to deal with this mess in Chapters 6 and 7, but we can fix a few things by setting the col_types argument in read_csv() to specify the column types for our two columns that were guessed wrong and skip the "junk" column. The argument col_types takes a list where the name of each item in the list is a column name and the value is from the table below. You can use the function, like col_double() or the abbreviation, like "l". Omitted column names are guessed.

| function | abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|

| col_logical() | l | logical values |

| col_integer() | i | integer values |

| col_double() | d | numeric values |

| col_character() | c | strings |

| col_factor(levels, ordered) | f | a fixed set of values |

| col_date(format = "") | D | with the locale's date_format |

| col_time(format = "") | t | with the locale's time_format |

| col_datetime(format = "") | T | ISO8601 date time |

| col_number() | n | numbers containing the grouping_mark |

| col_skip() | _, - | don't import this column |

| col_guess() | ? | parse using the "best" type based on the input |

# omitted values are guessed

# ?col_date for format options

ct <- list(

junk = "-", # skip this column

order = "i",

good = "l",

date = col_date(format = "%Y-%m-%d")

)

tidier <- read_csv("data/mess.csv",

skip = 2,

col_types = ct,

lazy = FALSE)## Warning: One or more parsing issues, call `problems()` on your data frame for details,

## e.g.:

## dat <- vroom(...)

## problems(dat)

problems()You will get a message about parsing issues when you run this that tells you to run the problems() function to see a table of the problems. Warnings look scary at first, but always start by reading the message. The table tells you what row (3) and column (2) the error was found in, what kind of data was expected (an integer), and what the actual value was (missing). If you specifically tell read_csv() to import a column as an integer, any characters in the column will produce a warning like this and then be recorded as NA. You can manually set what the missing values were recorded as with the na argument.

tidiest <- read_csv("data/mess.csv",

skip = 2,

na = "missing",

col_types = ct,

lazy = FALSE)Now order is an integer where "missing" is now NA, good is a logical value, where 0 and F are converted to FALSE and 1 and T are converted to TRUE, and date is a date type (adding leading zeros to the day). We'll learn in later chapters how to fix other problems, such as the min_max column containing two different types of data.

tidiest| order | score | letter | good | min_max | date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 | a | TRUE | 1 - 2 | 2020-01-01 |

| NA | 0.72 | b | TRUE | 2 - 3 | 2020-01-02 |

| 3 | -0.62 | c | FALSE | 3 - 4 | 2020-01-03 |

| 4 | 2.03 | d | TRUE | 4 - 5 | 2020-01-04 |

| 5 | NA | e | TRUE | 5 - 6 | 2020-01-05 |

| 6 | 0.99 | f | FALSE | 6 - 7 | 2020-01-06 |

| 7 | 0.03 | g | TRUE | 7 - 8 | 2020-01-07 |

| 8 | 0.67 | h | TRUE | 8 - 9 | 2020-01-08 |

| 9 | 0.57 | i | TRUE | 9 - 10 | 2020-01-09 |

| 10 | 0.9 | j | TRUE | 10 - 11 | 2020-01-10 |

| 11 | -1.55 | k | FALSE | 11 - 12 | 2020-01-11 |

| 12 | NA | l | FALSE | 12 - 13 | 2020-01-12 |

| 13 | 0.15 | m | TRUE | 13 - 14 | 2020-01-13 |

| 14 | -0.66 | n | TRUE | 14 - 15 | 2020-01-14 |

| 15 | -0.99 | o | TRUE | 15 - 16 | 2020-01-15 |

| 16 | 1.97 | p | TRUE | 16 - 17 | 2020-01-16 |

| 17 | -0.44 | q | TRUE | 17 - 18 | 2020-01-17 |

| 18 | -0.9 | r | FALSE | 18 - 19 | 2020-01-18 |

| 19 | -0.15 | s | FALSE | 19 - 20 | 2020-01-19 |

| 20 | -0.83 | t | FALSE | 20 - 21 | 2020-01-20 |

| 21 | 1.99 | u | TRUE | 21 - 22 | 2020-01-21 |

| 22 | 0.04 | v | FALSE | 22 - 23 | 2020-01-22 |

| 23 | -0.4 | w | FALSE | 23 - 24 | 2020-01-23 |

| 24 | -0.47 | x | FALSE | 24 - 25 | 2020-01-24 |

| 25 | -0.41 | y | TRUE | 25 - 26 | 2020-01-25 |

| 26 | 0.68 | z | FALSE | 26 - 27 | 2020-01-26 |

4.8 Glossary

| term | definition |

|---|---|

| base r | The set of R functions that come with a basic installation of R, before you add external packages. |

| categorical | Data that can only take certain values, such as types of pet. |

| character | A data type representing strings of text. |

| coercion | Changing the data type of values in a vector to a single compatible type. |

| csv | Comma-separated variable: a file type for representing data where each variable is separated from the next by a comma. |

| data type | The kind of data represented by an object. |

| deviation score | A score minus the mean |

| double | A data type representing a real decimal number |

| escape | Include special characters like " inside of a string by prefacing them with a backslash. |

| extension | The end part of a file name that tells you what type of file it is (e.g., .R or .Rmd). |

| extract operator | A symbol used to get values from a container object, such as [, [[, or $ |

| factor | A data type where a specific set of values are stored with labels; An explanatory variable manipulated by the experimenter |

| global environment | The interactive workspace where your script runs |

| integer | A data type representing whole numbers. |

| list | A container data type that allows items with different data types to be grouped together. |

| logical | A data type representing TRUE or FALSE values. |

| numeric | A data type representing a real decimal number or integer. |

| object | A word that identifies and stores the value of some data for later use. |

| operator | A symbol that performs some mathematical or comparative process. |

| panes | RStudio is arranged with four window "panes". |

| standard deviation | A descriptive statistic that measures how spread out data are relative to the mean. |

| tabular data | Data in a rectangular table format, where each row has an entry for each column. |

| tidy data | A format for data that maps the meaning onto the structure. |

| tidyverse | A set of R packages that help you create and work with tidy data |

| vector | A type of data structure that collects values with the same data type, like T/F values, numbers, or strings. |

| vectorized | An operator or function that acts on each element in a vector |

4.9 Further Resources

- Data Organization in Spreadsheets (Broman & Woo (2018))

- Chapter 11: Data Import in R for Data Science

- RStudio Data Import Cheatsheet

- Codebook Package Comparison

- How to automatically document data with the codebook package to facilitate data reuse (Arslan (2019))

- Skimr